Gordon Monro — Eureka: Singular and Plural (Installation)

The Eureka Centre in Ballarat is devoted to commemorating the Eureka rebellion in Ballarat in December 1854, when the pick-and-shovel gold miners took up arms against an oppressive police force; the revolt was put down bloodily. The Centre engaged me to create a a temporary installation, a new generative art work using data from the events of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion. Eureka: Singular and Plural is my response.

Anthony Camm, who leads the Eureka Centre, has described Eureka as a meso-scale event: not just the concern of a few individuals or a single family, but not so large as to involve whole nations either. Many names of individuals involved are known, and in some cases extensive biographical detail.

The Eureka rebels demanded an end to the high tax they were subjected to in the form of a mining licence fee. But they also demanded political representation and the right to vote, and an end to corrupt and dishonest official behaviour. The Eureka rebellion took place in revolutionary times; some of those involved had connections with the Chartist movement in England and the upheavals that took place across Europe in 1848. Although the Ballarat rebellion was suppressed, in the end most of the movement's demands were met.

At the same time that the social revolution was occurring, a technological revolution was unfolding. The first steam train service in Victoria began in 1854, the year of the Eureka rebellion; also in 1854 the first electric telegraph service started in Victoria. The telegraph line reached Geelong (a sea port south-east of Ballarat) at the start of December 1854, and the first message sent from Geelong to Melbourne by the new telegraph was news of the Eureka battle. If the telegraph had been available in Ballarat at that time, the fight and loss of life might well have been averted.

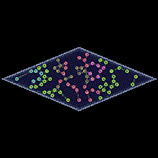

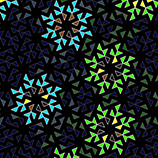

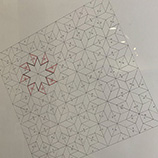

In making the work I wished to honour the individuality of those involved in the Eureka events, but also to represent in some way the greater forces, social and technological, that had these individuals in their grip. The main part of the work is a large abstract print based on a mathematical construction called an Ammann-Beenker tiling. This never repeats, but is not random; it is based on definite rules, but it is hard to see what they are; a metaphor for the larger pattern the individuals of Eureka were enmeshed in. I chose this specific pattern because it includes whole and fragmented eight-pointed stars. The Eureka flag, the central symbolic artefact of the rebellion, flown by the rebels at Eureka and now displayed at the Eureka Centre, has eight-pointed stars.

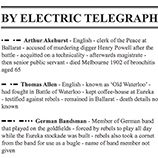

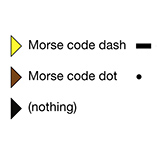

For each of the 75 individuals represented in the work I have provided an extremely short and "telegraphic" biographical note. Each individual is also represented by a coloured "rosette" in the large print; the rosette has encoded in it the Morse code for the initials of the individual. There is also a key to Morse code, so the rosette can be connected with the biography of the person it represents.

The discussion of the Eureka rebellion is always framed in terms of a social revolution; in introducing Morse code my intention is to draw attention also to the parallel technological revolution that was intertwined with the social revolution.

Materials: Digital print 213 x 500 cm, printed as vinyl wall-hanging. Panel 80 x 160 cm with 75 short biographies. Preliminary drawing, pencil on card, 63 x 51 cm (exhibited as part of the installation). Key to Morse code and the rosettes.

This exhibition was commissioned by the Eureka Centre Ballarat. The Eureka Centre is located at the site of the 1854 Eureka Rebellion and is a cultural facility of the City of Ballarat.

The pattern underlying the main panel of the work is also used in the print Alogos: Maze of Triangles.